Printmaking—the act of transferring an image from one source to another surface to create multiple copies of the original image—is an ancient art form.1 This publication highlights a collection of fine art prints gifted to the Petrie Institute of Western American Art by collector, curator, and author Barbara J. Thompson. The prints feature diverse representations of the people, animals, architecture, and landscapes of the American Southwest by Anglo-American artists from the late nineteenth through the twentieth centuries. This essay establishes the historical context in which these artists worked. The sections following this essay focus on specific techniques—intaglio, lithograph, block print, and serigraph—which deeply inform the production and appearance of each print. Finally, this companion guide includes the transcript from an interview with Thompson and a list of all prints included in the Thompson Collection at the Denver Art Museum.

Prior to the nineteenth century, few artists produced printed pieces for individual sale as works of art; rather, most printed material was used as illustrations for books or magazines. This began to change by the mid-1850s, when, in Europe, a new generation of artists utilized printmaking to make handsome copies of their paintings and realized how printmaking lent itself to certain subject matter such as landscapes, city views, and genre scenes to create original artworks. By the late 1870s, the popularity of prints spread to the United States, where etching clubs were forming in various cities from New York to Cincinnati.2 By the 1880s, several American artists had made a name for themselves in the art world as engravers, including Peter Moran (1841–1914).3

Moran was among the first known Anglo-American artists to visit the Southwest, a relatively small geographic area of the US comprising primarily New Mexico and Arizona but with porous boundaries extending into the surrounding states.4 The American Southwest has always been a place of great cultural diversity, beginning with the Native Americans who called it home for centuries before the Spanish colonists arrived, and eventually the Anglo-Americans who moved west from the East Coast. When Moran traveled to the region, first in 1864 and again in 1883, the area was still primarily inhabited by Native Americans and Spanish descendants who farmed or herded animals much as previous generations had.

Moran’s Threshing Harvest, San Juan New Mexico depicts part of the annual wheat harvest of the Taos Pueblo, which he witnessed on his 1883 trip.5 Threshing was a necessary step in processing wheat for consumption. Large piles of grain were heaped into the center of several circular enclosures about the size of a circus ring made of several long wooden poles driven into the ground. Horses were driven around this ring at a great pace, which jostled and crushed the grain, separating the edible part from the straw.6 Moran created a version of this event, which, while based on what he observed first-hand, was highly dramatized. The horses, normally contained in an enclosure for this task, run loose at a furious pace, kept in check only by the vigilant Puebloans cracking their whips. Moran utilized the medium of etching to heighten the energized feeling of the work by carving many short, quick lines into the prepared metal engraving plate.7 He built up the lines through crosshatching. Because of the way the engraved lines of the plate hold and release ink through the printing process, greater subtleties of tone can be produced. This allowed for the deep blacks of the horses and the rich variety of clouds across the sky.

It would be more than a decade before other Anglo-American artists filtered into the Southwest. The Taos Society of Artists, a group formed for the benefit of promoting the work of members through traveling group exhibitions, was highly influential to the creation of an art scene in Taos.8 A number of the Taos Society artists, such as W. Herbert “Buck” Dunton (1878–1936) and E. Martin Hennings (1886–1956) embraced printmaking.9 A similar collective group of artists joined together in Santa Fe. Their exhibitions also began in 1915 and included prints by Will Schuster and, by the 1930s, Arthur Hall and Norma Bassett Hall.

Another boon to the art scene of the Southwest, and in particular to the artist groups of Taos and Santa Fe, was a promotional campaign developed by the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway (ATSF, or often simply the Santa Fe). The railway was first chartered in 1859 to connect the towns of Atchison and Topeka, Kansas, with Santa Fe, New Mexico. It reached New Mexico in 1878. To market their new railway, the ATSF commissioned well-known artists to make trips via their train, paying them primarily in free tickets and accommodations in hotels along the route. Artists created paintings of the people and landscapes they saw, and many of these paintings were reproduced as advertisements for the railway. This created new markets of tourists both for the Santa Fe Railway as well as for the artists whose work they reproduced.10

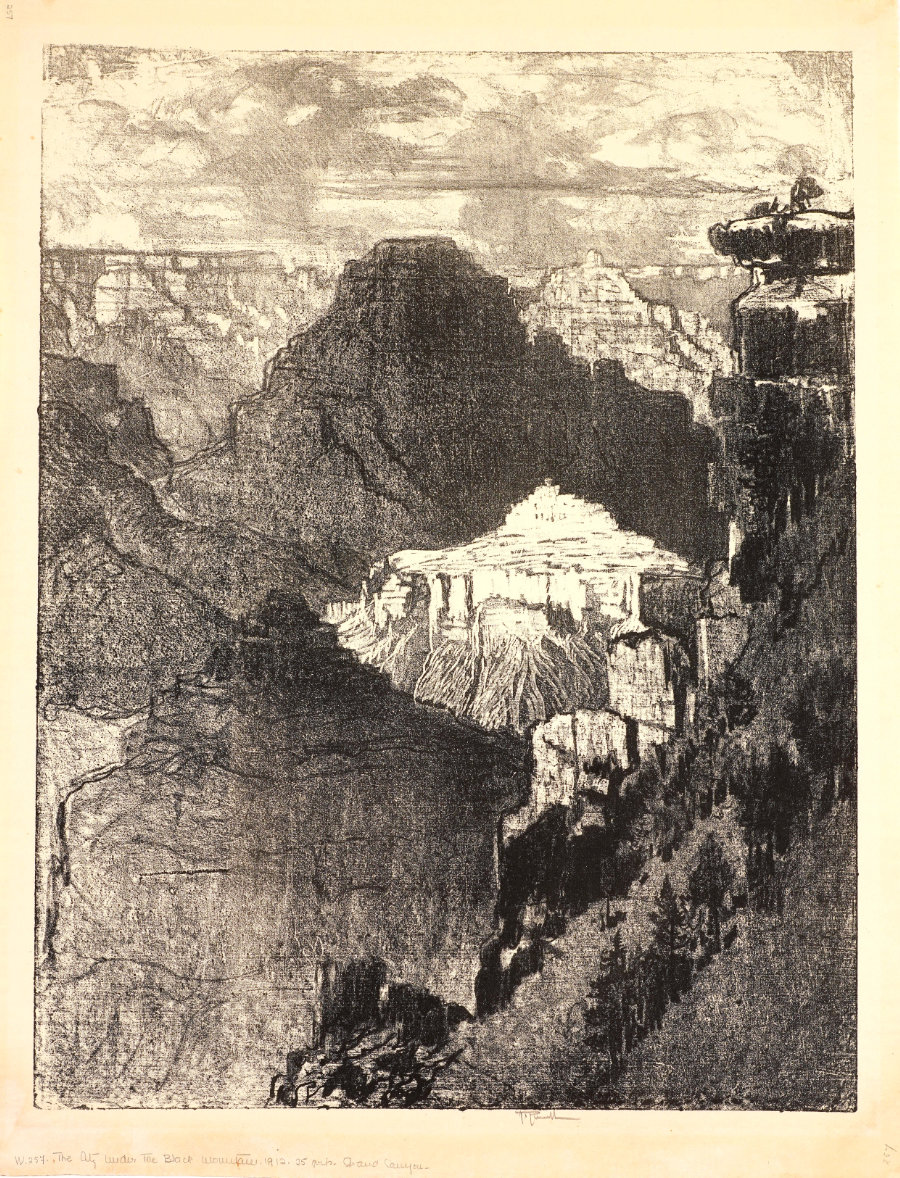

Despite the influx of artists visiting the Southwest during the last decades of the nineteenth century and the first decade of the twentieth, there were still some such as Joseph Pennell (1857–1926) who could say after his first trip west in 1912 that Yosemite and the Grand Canyon were “too wonderful and suggestive and inspiring for words, and no one in painting and drawing has touched it.”11 Pennell’s lithograph The City Under the Black Mountain is a scene of the Grand Canyon where he makes use of the canyon’s shifting light to focus the viewer’s eye on a sunlit rocky outcrop evoking a white city on a high mesa surrounded by black mountains. Lithography relies on the fact that oil and water do not mix. An image is drawn with an oily crayon or pen. This oily image is then transferred onto a flat surface, usually a slab of smooth limestone that has been treated with a water-based solution. Using the pressure of a printing press, the inked stone is pressed against a piece of paper. The oily ink transfers to the paper, creating a mirror image of the work on the stone.12 In The City Under the Black Mountain, Pennell creates the lines of rocks with the flowing movements of a crayon on paper. The white lines of the “city” are created by erasure rather than addition. Pennell drew onto a specially prepared paper and brought his drawings of the Grand Canyon to a professional lithographer when he next came to a town with a printing studio.13

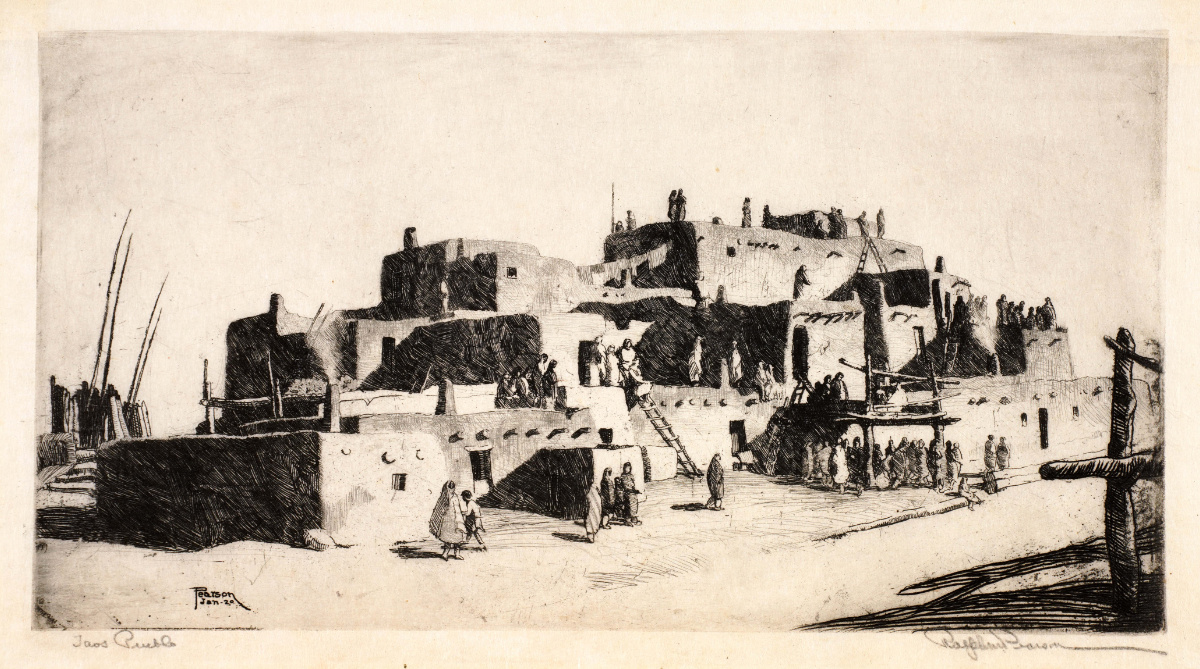

Ralph M. Pearson (1883–1958) was born in Iowa but spent many years in Chicago, where he knew of and was originally heavily influenced by Pennell.14 However, the Armory Show of 1913, which was on display in New York and Chicago and featured European modernism, inspired him to experiment with form and design. Around 1919, he came to New Mexico and settled on a ranch just south of Taos, where he set up one of the area’s first printing presses and had a successful greeting card company for several years. In Taos Pueblo from 1920, Pearson presents a recognizable subject but hints at modernism by isolating the pueblo from the landscape and stressing the deep shadows created by the bright southwest sun, which reduces the structure to stacked blocks of ink. What first appears to be fine details upon closer inspection dissolves into shapes—the people in the scene are mostly suggestive oblong objects, and the wooden beams projecting from the sides of the adobe are only a few lines presented in a way to trick the viewer’s eyes into believing their solidity. To this engraving, Pearson has added some drypoint engraving, giving some details, like the fence at bottom right, a velvety tone. The process of drypoint uses a very sharp, finely pointed tool, held much like a pen, to scratch lines onto the plate. The lines are very shallow, but they produce a burr, a small bit of metal shaving resulting from the metal being pushed out from the scratched line. This burr holds the applied ink in a different way than an etched or engraved line, creating a fuzzy edge as opposed to a solid one.15

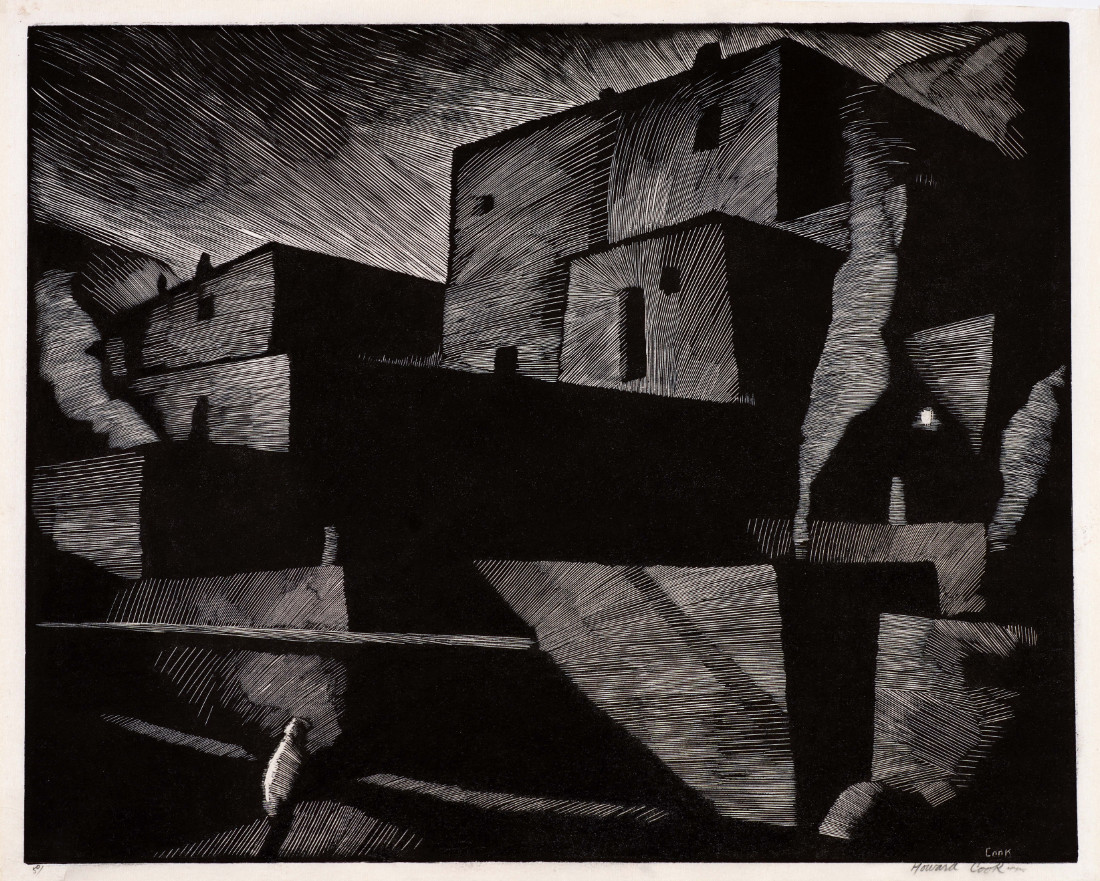

In 1925, Howard Cook (1901–1980) came to New Mexico on an assignment from Forum Magazine to illustrate Willa Cather’s book Death Comes for the Archbishop. In his woodcut Moonlight Pueblo from 1927, Cook, like Pearson before him, was inspired by the local adobe architecture, but he employed wood block engraving to create his night scene. Cook carved his image into a plank of wood—the carved lines became the white negative spaces, and the black areas were left untouched, essentially creating a stamp. By composing an image with so much dark space, he could easily produce a night scene by leaving large areas alone. His talent with the medium is seen in how finely he carved out the white lines. Each thin line would leave fragile slivers of wood on either side to hold the ink. If one were damaged, gaping white holes would result.16

By this decade, the advertising efforts of companies such as the Santa Fe Railway had found great success, and tourism boomed in the area. John Sloan (1871–1951), a member of the modern New York–based art group known as The Eight, visited the Southwest on an annual basis to glean inspiration and created works including Indian Detour from 1927. In this raucous scene, stylishly dressed women in cloche hats and knee-length dresses and dapperly dressed men chat with each other, dance, look at a Catholic shrine, and watch Native Americans dancing. Along the periphery, inhabitants of the pueblo watch the tourists watch the dancers. Perhaps unknowingly, the tourists have become part of the spectacle.

In just a few years, such a scene would be hard to imagine amid the bleakness of the Great Depression, during which time the market for fine art started to dry up. Relief finally came after President Franklin D. Roosevelt initiated the New Deal and with it an arts division that helped keep artists employed and regularly fed. Over the years, several programs focused on artists, with the best known being the Federal Arts Program (FAP), sponsored by the Works Progress Administration (WPA), in 1935.17 The FAP/WPA commissioned artists to paint murals across America in post offices, libraries, schools, and government buildings. The Graphics Division supported the production of prints, which were sold affordably to broad audiences.18 It also set up sixteen graphic workshops where artists could access presses, although, unfortunately for artists in the Southwest, there was not a single graphic workshop between Illinois and California. Some printmakers who lived in the Southwest year-round were lucky enough to own a press or have access to a private printing press.19

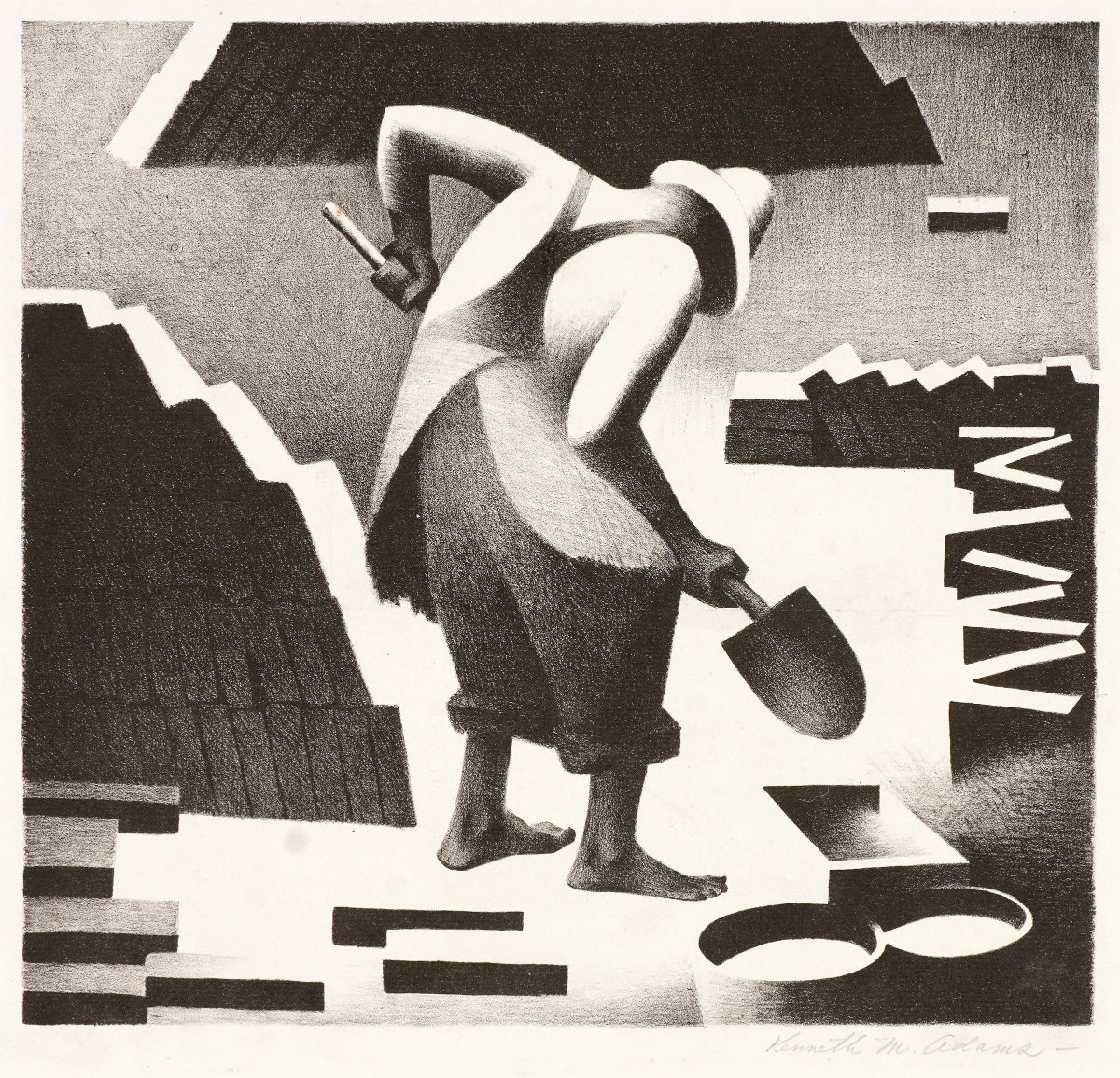

Other artists, like Pennell decades before, brought their prints back to cities that had printing studios. After his earliest Southwest sojourns, the first of which was in 1924, Kansan Kenneth Miller Adams (1897–1966) brought his blocks to Wichita to be printed at the Western Lithograph Company. 20 Adams became interested in lithography around 1929, and by the 1930s, his subjects were often laborers, which spoke to the broader social zeitgeist of the Great Depression. In Brick Maker, a lithograph from about 1931, Adams portrays a single figure filling a brick mold. His bent back emphasizes the weight of his task. He has been productive. Piles of bricks create sharp-edged geometric forms, including a zig-zagging line on the right. The man is a study in contradiction. His softly rendered form contrasts with the angularity of the bricks around him, while his deftly and realistically depicted feet are foils for the simple square hands holding the shovel.

Besides the FAP/WPA, there were nongovernment–funded ways for artists to have their works seen by a greater audience. One was the American Artists Group (AAG), a greeting card company started in 1934 by businessman Samuel Golden and the art critic and curator Carl Zigrosser. The mission statement in their 1935 handbook states, “The purpose of the American Artists Group is to popularize American art by making it better known to the American public. One way, and a practical way, to accomplish this purpose, is, to distribute as widely as possible first-class reproductions of worthy originals.”21 With Zigrosser’s expert eye, they were able to commission works from a variety of artists across the country and bring their art into thousands of households.

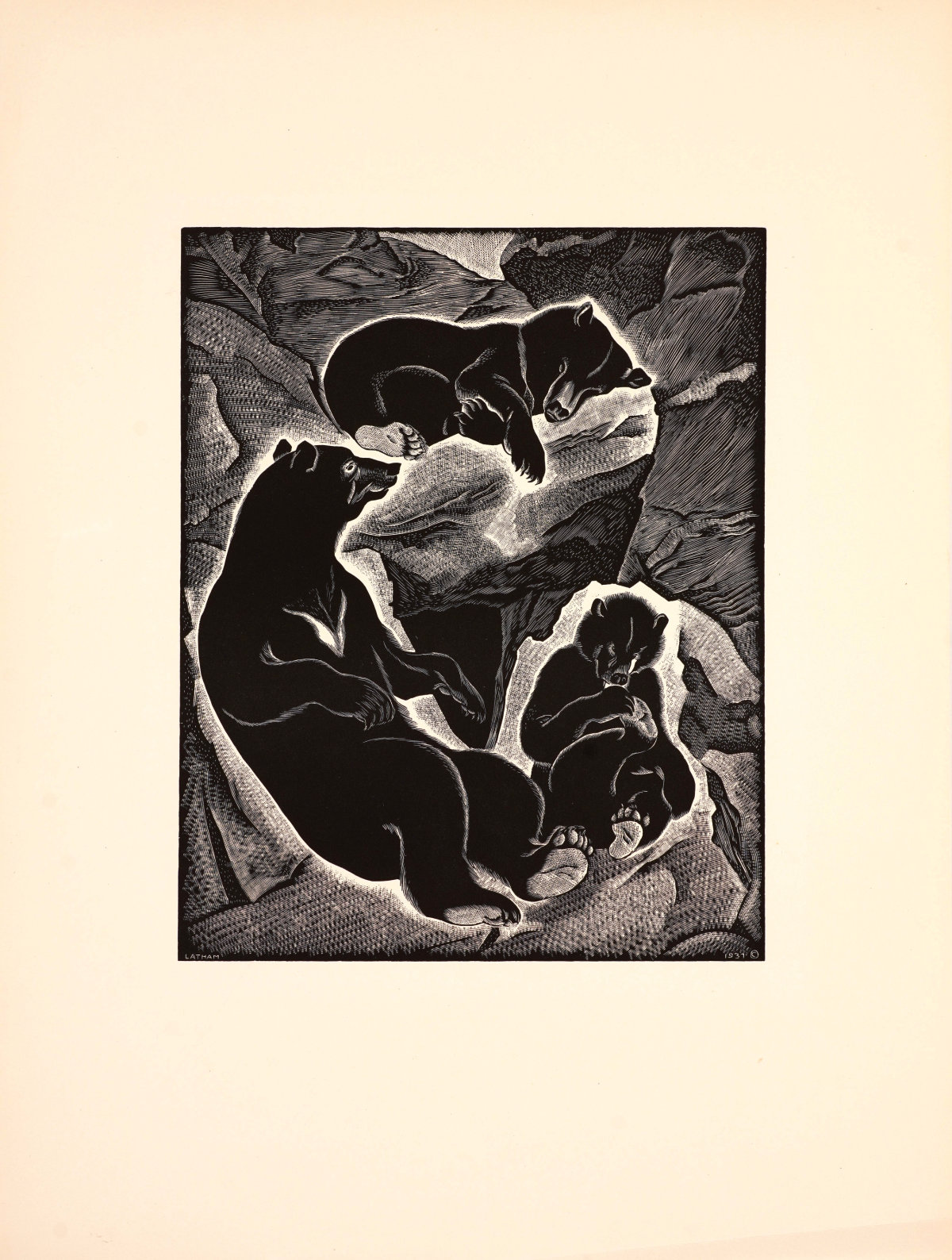

One of the artists commissioned by the AAG was Barbara Latham (1896–1989), the wife of Howard Cook. In her woodcut engraving Bears from 1937, she uses wood engraving tools inherited from her great uncle to create a rich variety of textures.22 The subject matter is playful, and the circular composition of the bears in their den instills a sense of safety and well-being. The comforting subject matter fit nicely with the AAG’s general approach of commissioning works that would appeal to a broad range of people.

From the beginning of the New Deal, printmakers working for the Graphics Division were recruited to create posters supporting President Roosevelt’s vision for turning the depressed economy around.23 With the beginning of the Second World War and the eventual engagement of the United States in 1941, the FAP/WPA projects focused increasingly on the war effort. The Graphics Division popularized a method of printmaking called silk screening. This streamlined the production of posters, which previously relied on less efficient methods of hand-lettering and coloring.24 During the 1930s and through the end of World War II, more and more artists began using the process to create fine art prints. Artists preferred the term serigraphy, differentiating it from the silk-screening process used to create mass-produced works.25 Since the process was less laborious and required less equipment than other printmaking techniques, it was perfect for an area such as the Southwest, which was lacking in print studios.26 All one needed was a fine mesh screen stretched within a frame, ink, and a squeegee. After placing stencils or a blocking agent on the screen, ink is forced through the screen onto a piece of paper using a squeegee. Complex images are built out of the layering of several screens printed individually and left to dry between additions.

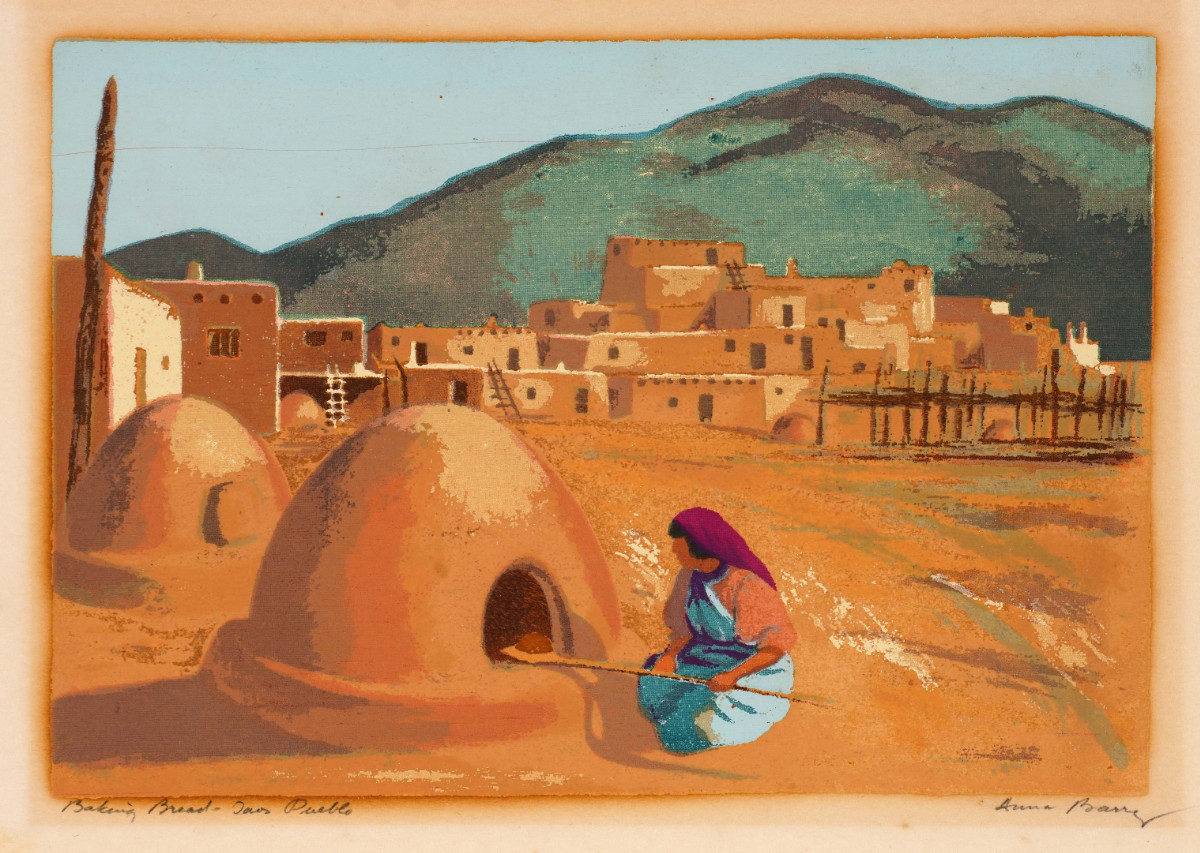

In the 1946 serigraph Baking Bread—Taos Pueblo by Anna Barry (1907–2001), a woman bakes bread in an horno, a traditional mud-constructed outdoor oven. The print includes at least seven colors, meaning seven different screens were used to create it. The layering of certain colors is seen in the mountain in the distance, where brown and green overlap; in the combination of the dark blue of the woman’s dress and the light cream of the sun’s highlights; and in the adobe structures, where oranges and browns have been overlaid. While the printing process was simple, the thought and preplanning required to make such an image was not.

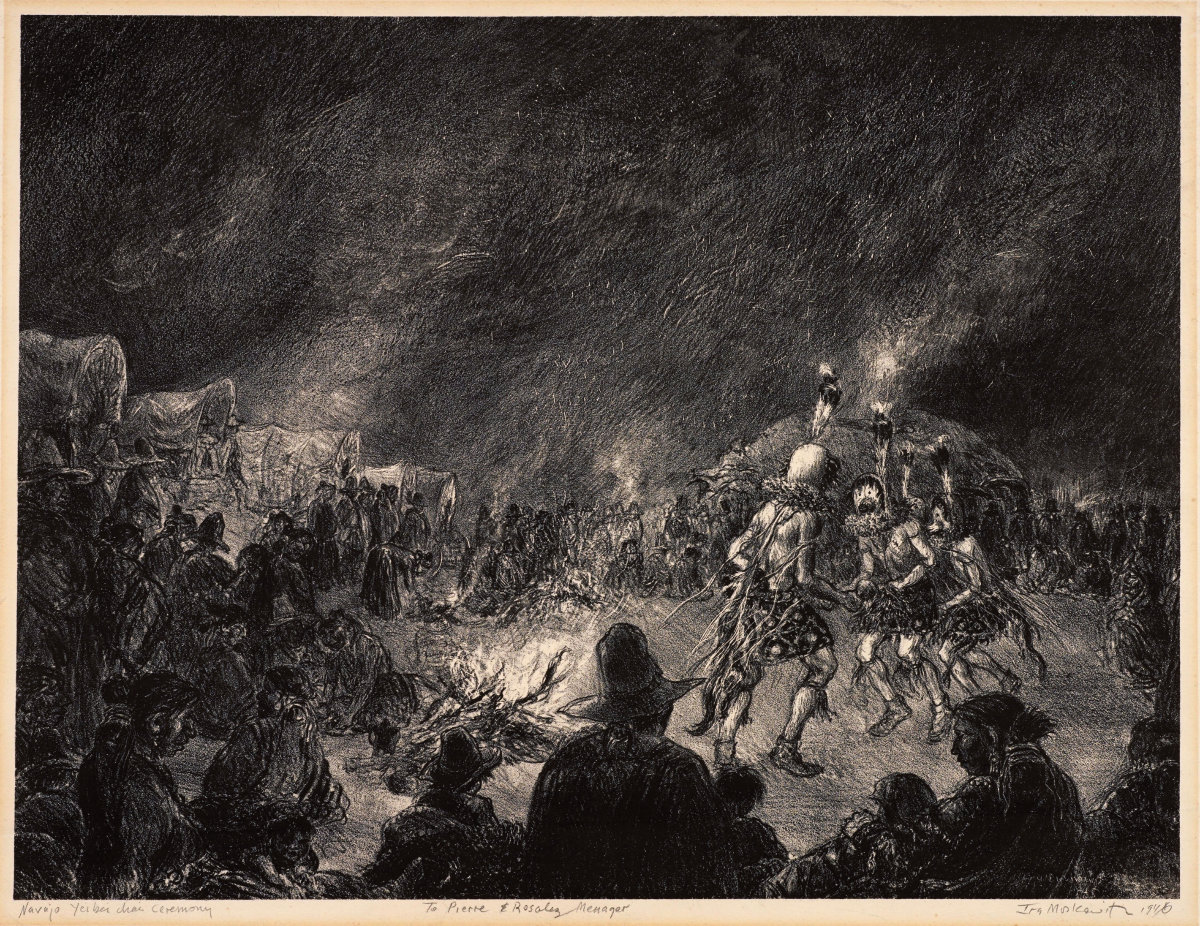

Barry’s husband, Ira Moskowitz (1912–2001), also often focused on Native American subjects. After the couple moved to New Mexico in 1944, Moskowitz regularly observed Indigenous culture, finding its rootedness in history and spirituality a countermeasure for the problems that he perceived plagued the mid-twentieth century.27 During this time, the population of New Mexico increased in part because of federal personnel who moved with their families to such facilities as the Los Alamos National Laboratory and the Roswell Air Force Base. Though the Second World War had ended, the Cold War was just beginning. In Navajo Yeibei Chai Ceremony from 1945, animated figures move through a darkened space.28 Moskowitz’s engagement with such subjects was a foil against the new and unsettling atomic age. During a time of unease, they grounded him, and perhaps viewers of his work, in a deeper sense of human history via representations of traditional Native American ceremonies.

Gene Kloss (1903–1996), a resident of New Mexico since 1929, had been perfecting her craft over the years by the time she combined the two intaglio methods of drypoint and aquatint to create Taos Eagle Dancers in 1955. The speckled quality of the background, along with the darker tones of the dancers’ skin and the feathers they wear, is a result of those areas of the metal plate being dusted with a finely powdered form of tree sap resin or asphaltum.29 Drypoint is employed to create fine linework detailing the figures’ faces, hair, and clothes, while instilling a soft velvet tone to the feathers. Unlike Moskowitz, who situated his dancers firmly in a certain time and place, Kloss pulls her dancers out of context, placing them in a soft gray space created by the aquatint, lacking even a floor to dance upon. The effect is one of weightlessness, as if the dancers were becoming the eagles they are meant to represent.30

Artists like Kloss, who had been living in the Southwest for decades, saw the area change over time, from a relatively unpopulated place (which Joseph Pennell declared to be where “no one in painting and drawing has touched”) to one of paved roads and artist colonies.31 Throughout the decades and the myriad changes, the artists represented in the Barbara Thompson Collection understood the allure of the Southwest and remained dedicated to its people, landscapes, and wildlife. In this collection, Thompson allows new generations of viewers to appreciate a particular part of our world through expertly executed carved and printed lines, each one its own impression of the American Southwest.

Notes

-

For more information on the history of printmaking, see Norman Kent, “A Brief History,” in The Relief Print: Woodcut, Wood Engraving & Linoleum Cut, eds. Ernest W. Watson and Norman Kent (Watson-Guptill Publications, 1954); Antony Griffiths, Prints and Printmaking: An Introduction to the History and Techniques (University of California Press, 1996); William M. Ivins Jr., revised by Marjorie B. Cohn, How Prints Look (Beacon Press, 1987); Bamber Gascoigne, How to Identify Prints (Thames & Hudson, 2004); and Arthur M. Hind, An Introduction to a History of Woodcut (Dover Publications, 1963). ↩︎

-

James Watrous, A Century of American Printmaking: 1880–1980 (University of Wisconsin Press, 1984), 1–7. ↩︎

-

Peter Moran was the youngest brother of painter and engraver Thomas Moran (1837–1926). ↩︎

-

Clinton Adams, Printmaking in New Mexico, 1880–1990 (University of New Mexico Press, 1991), 3. ↩︎

-

Moran traveled with journalist Henry R. Poole, and his account of the Taos Pueblo harvest can be read in “A Harvest with the Taos Indians,” in The Continent 3, no. 15 (1883): 449–58. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 453. ↩︎

-

The darkness of the lines could be developed through how lightly the artist cut into the ground, an acid-resistant coating that had been applied to the metal plate, or how long he left certain areas in the acid bath the plate was put into. It is the acid bath that would physically cut into the plate, creating the grooves that would hold the ink that would then be transferred onto the paper. For more information about the etching process, see Ivins, How Prints Look, 45–46; Gascoigne, How to Identify Prints, 9–11; and Judy Martin, The Encyclopedia of Printmaking Techniques: A Comprehensive Visual Guide to Traditional and Contemporary Techniques (Sterling Publishing Co., Inc., 2002), 84–93. ↩︎

-

Charles C. Eldredge, “Introduction,” in Art in New Mexico, 1900–1945: Paths to Taos and Santa Fe (Abbeville Press, Inc., 1986), 11. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 3. The inclusion of several printed works in the 1913 Armory Show in New York had a positive influence on people’s willingness to embrace printmaking, which at times had been viewed as unprofitable, old-fashioned, and too commercial. ↩︎

-

Keith L. Bryant Jr., “The Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway and the Development of the Taos and Santa Fe Art Colonies,” Western Historical Quarterly 9, no. 4 (1978): 436. ↩︎

-

Joseph Pennell to Dr. John C. Van Dyke, quoted in Elizabeth Robins Pennell, The Life and Letters of Joseph Pennell, vol. 2 (Little, Brown and Company, 1929), 108. ↩︎

-

The water-based solution is made of gum arabic, and this solution is absorbed by the whole surface except for the parts with the oily image, which has the effect of making the non-drawn-on portions even more water-absorbent and completely repellent to accepting any ink applied to the stone. The stone is then wiped down with turpentine to remove any excess greasy drawing material, but a very fine film of it is left tightly bound to the stone surface. This film will now easily accept an oil-based ink, but the water-dampened remainder of the surface will repel the ink spread on the stone. For more information on the lithographic process see: Gascoigne, How to Identify Prints, 19; Archibald Standish Hartrick, Lithography as a Fine Art (Oxford University Press, 1932), 61–71; Martin, The Encyclopedia, 110–23. ↩︎

-

Joseph Pennell to Mr. Robert Underwood Johnson, quoted in Elizabeth Robins Pennell, The Life and Letters, 109. Many lithographers did not print their own works but relied on established studios to help them with the printing process. The transfer paper was typically coated with a gelatin substance. The artist would then draw on it as they would the limestone. When it came time to print, the paper would be wetted and placed down on the stone. The gelatin and the paper backing could be washed away while the inky drawing would stick to the stone. For more information on transfer lithography, see Gascoigne, How to Identify, 20. ↩︎

-

Pearson came to New Mexico around 1919 and settled on a ranch just south of Taos, where he set up one of the area’s first printing presses and had a successful greeting card company for several years. ↩︎

-

Griffiths, Prints and Printmaking, 76. This fuzzy effect can create a rich black tone, but because the burrs created are delicate, only a few prints can be pulled before the pressure of the press flattens the burr, reducing its ability to hold ink. ↩︎

-

For more information on the process and history woodblock printing, see Douglas Percy Bliss, A History of Wood Engraving (Skyhorse Publishing, 2013); and Arthur M. Hind, An Introduction to a History of Woodcut, vol. 1 (Dover Publications, 1963). ↩︎

-

The first program was the short-lived Public Works of Art Project (PWAP), which only lasted from December 1933 to May 1934. ↩︎

-

One of the ways the FAP/WPA promoted the work of their Graphic Division was to set up exhibitions in public spaces, including schools, libraries, and hospitals. ↩︎

-

Phillips Kloss, Gene Kloss Etching (Sunstone Press, 2000), 11. Gene Kloss (1903–1996) was one of the lucky ones who owned her own press, which she bought from the defunct holiday card company Pearson had once owned. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 143n4. While public print shops opened throughout the country during the Great Depression, Western Lithograph, which had been founded in the early 1920s by C. A. Seward (1884–1939), was instrumental and ahead of its time for establishing a communal printing location open to many artists. See George C. Foreman and Barbara Thompson O’Neill, The Prairie Print Makers (The Kansas Arts Commission, 1981) for more information on C. A. Seward and the Western Lithograph Company. ↩︎

-

Samuel Golden, Handbook of the American Artist Group (American Artists Group, 1935), 7. Some of the works were turned into greeting cards, while others were sold as larger stand-alone limited-edition prints. ↩︎

-

Barbara Lathan, “Oral Histories,” interview by Susan Cooper, unpublished, 1976, audio, tape 2b, 0:01:36, Denver Art Museum. Such patterning could be achieved by carving into a denser end cut of wood, versus a softer plank-wise cut normally used in wood block engraving. The greater density allowed for finer cuts and greater detail. ↩︎

-

Posters served a variety of purposes, including public service announcements, general education concerning new policies, promoting material meant to alleviate some of the emotional burden experienced , and promoting events put on by other parts of the WPA, such as its Music and Theater Divisions. ↩︎

-

Meg Miller, “How the WPA Popularized Screen Printing,” Fast Company, April 13, 2016, https://www.fastcompany.com/3058863/how-the-wpa-popularized-screen-printing. When the artist Anthony Velonis (1911–1997) was hired by the Civilian Work Administration in New York, he came up with the idea of using a method of mass production that had previously been used mostly for patterning textiles and large backgrounds for department store windows. ↩︎

-

Arpie Gennetian, “WPA Posters: Art for the Common Good,” Objectives, no. 5, 2021, https://adht.parsons.edu/historyofdesign/objectives/wpa-posters/. Velonis coined the term, with “seri” being the Latin for silk and “graphein” being the Greek for to write or draw. Carl Zigrosser is credited with popularizing the term in his writings. ↩︎

-

Adams, Printmaking in New Mexico, 40; and Peter Bermingham, The New Deal in the Southwest: Arizona and New Mexico (University of New Mexico), 29. ↩︎

-

Joseph Czestochowski, The Drawings and Paintings of Ira Moskawitz (Landmark Books, 1990), 16. ↩︎

-

“Yei Bi Chei (Yébîchai) Night Chant-First Day,” Navajo People: Information about the Diné (Navajo People), Language, History, and Culture, accessed November 5, 2024, https://navajopeople.org/blog/yei-bi-chei-night-chant-first-day/. The Yeibei Chai (or Yeibechai) ceremony was a healing ritual spanning nine days. For the first eight days and nights, the dancers and singers administer their medicine privately, but on the ninth night, the rest of the tribe is invited to watch the ceremony, which is most likely what Moskowitz is portraying in this print. ↩︎

-

Donald Saff and Deli Sacilotto, History and Process of Printmaking (Holt, Rinehart and Winston, Inc., 1978), 141–47. The dust settles on the plate in a thin layer and is then heated to adhere the powder to the plate. Like other forms of etching, a stopping agent can then be applied to the areas needed to be kept away from the acid bath. ↩︎

-

Eagle dances were done in connection to a variety of ceremonies. Eagles were thought to be close to the sky gods since they could fly so close to the sun. Mimicking the “dance” they do in the air was meant to help invoke the gods in whatever capacity the main ceremony called for. ↩︎

-

Joseph Pennell to Dr. John C. Van Dyke, quoted in Elizabeth Robins Pennell, The Life and Letters, 108. ↩︎